Women wearing Women

18th-Century Women’s Accessories as Expressions of Female Friendship

By Roxane Hemard | 14 February 2024

Portrait miniatures’ highly detailed, jewel-like quality and portability, made for personal purposes both secret and acknowledged, gives them an almost incomparable intimate quality. 18th-century portrait miniatures, often housing relics like hair in a glazed reverse to the locket, are commonly perceived as private mementos, reflecting sentiments of love and remembrance. Despite the inclination to view portrait miniatures as exclusively private, they were, in fact, external signs of social status and expressions of feelings, loyalty, or propaganda. As objects exchanged between individuals, they played a crucial role in the culture of memory, [1] evident in ceremonial contexts of courtship and dynastic representation. It was an object that was given and received, carried and manipulated, evoking a social bond between wearer and object. However, amidst the narratives of political intrigue, familial and romantic love, one crucial aspect often overlooked is the profound influence of female friendships within the market of portrait miniatures. Contrary to assumptions, not all owners were entangled in romantic complications; rather, the changing fashion styles and advancements in enamel techniques [2] elevated the culture of visibility and value of miniatures.

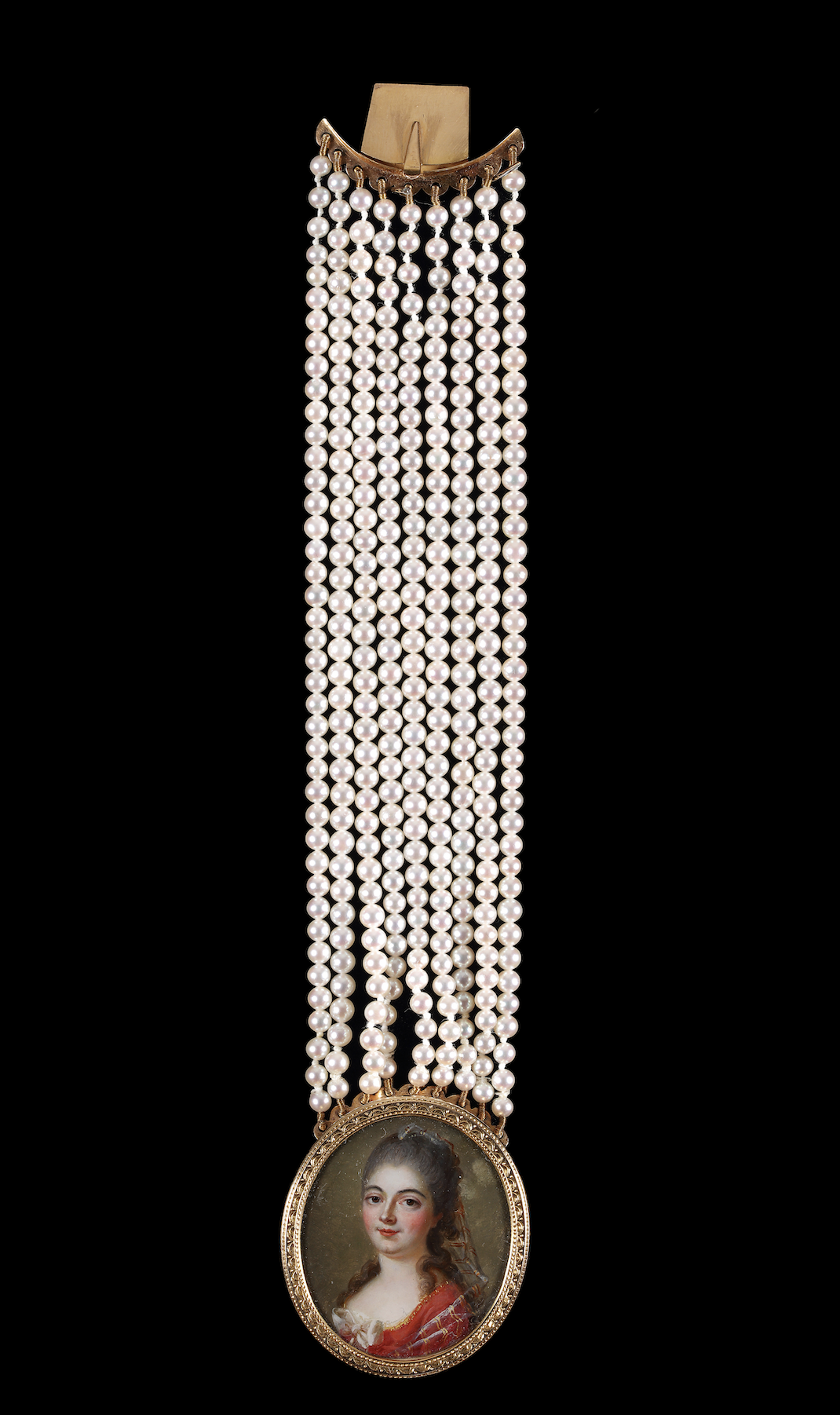

Women, the primary owners and wearers of portrait miniatures, fueled a vast market of luxury goods, openly showcasing precious tokens as jewellery, including bracelets, necklaces, pendants, or prominently displayed on the body in completely other ways. [3] A rare 18th-century example of such bracelets (Fig. 1), painted by Arnaud Vincent de Montpetit in fixé-sous-verre [4] (fixed underglass), can be seen below. The focus here, however, is not on jewellery, an already highly researched topic which most often revolves around notions of romanticism or intimacy, and most often gifted by men. Instead, my attention will focus on female accessories, namely Étui or Nécessaire, lace-making Shuttles, and Carnet-de-bals. Excluding snuff boxes, traditionally associated with betrothal, weddings or political gifts, our focus narrows to gifts often exchanged between women.

Women seized opportunities to commission functional luxury objects with or without the incorporation of portrait miniatures of their closest female friends. Within the aristocracy, a class whose social relations relied heavily on visibility and publicity, inseparable friendships inhabited a more public arena than friendships within the bourgeoisie. [5] These objects became badges of sentiment, and the trend of exchanging accessories became the means of creating value and empowering female relationships. There has surprisingly been little to no scholarship on these fascinating objects, referred to as mere examples of female domestic social culture or simply alternative ways miniatures were set. However, material culture deeply informed and expressed female friendships, and helped create gendered and stratified social spaces and relationships. [6]

Fig 2. The most common adornment was oval medallions, most often with coats of arms but also including scenes with physiological connotations. This beautiful knotting shuttle by Jean-Joseph Barrière (1772), now in the Wallace Collection, is decorated with oval medallions of chased gold bagpipes, arrows and torches as well as a medallion of a girl with a dancing dog being watched by two boys. Embedded within a feminine accessory of luxury and pleasure, the portrayal is a reminder of her being watched.

Shuttles

The art of knotting or the creation of ornamental strings emerged as a prominent practice among upper-class women. The knotting process involved the use of a specialised tool, the knotting shuttle, allowing the user to wind thread gradually, transforming it into long strings of decorative knots. Silk thread or cord, wrapped around the shuttle, was unwound as needed to create decorative braids, forming patterns suitable for stitching onto clothing or other items. This intricate craft became a staple of the leisure activities of affluent women, who dedicated hours to meticulously crafting delicate knots with exquisitely adorned shuttles. Knotting shuttles themselves were objects of luxury, crafted from expensive materials such as tortoiseshell, crystal, mother-of-pearl, and silver. Some, like the exceptional examples below, even featured gold and delicate enamel work, amplifying the status of the woman who owned them. Despite the ornamental nature of surviving examples, adorned with landscapes or scenes of cherubs and shepherdesses rather than portrait miniatures, I use them as a starting point to explore the gift-giving market of luxury goods among women. [7]

Fig. 3 Jean-Étienne Liotard (1702-1789), Archduchess Marie Antoinette of Austria (1755-1792), at age seven, holding a netting shuttle, 1762, watercolour and pastel, Musée d’Art d’Histoire de Genève

The widespread popularity of knotting during the 17th and 18th centuries positioned it as a prevalent subject in women’s portraiture from that era. More than a mere craft, knotting became a symbol of femininity and domesticity. Jean-Etienne Liotard’s portrait of Marie Antoinette (Fig. 3) in 1762 as well as Jean-Marc Nattier’s portrait of Madame Adelaide de France (Fig. 4) showcase women using a knotting shuttle, reflecting their gendered roles alongside their noble status. During this period, the notion of women returning to the private sphere was promoted; the ‘virtuous woman’ becoming synonymous with the ‘domestic woman’, regardless of her social ranking. [8] The integration of knotting shuttles into larger female portrait paintings therefore added a layer of political hype to the artwork. However, this unique approach allowed the model to resonate with the craft, transforming the shuttle into a more revealing object within the overall composition. Depictions of women with shuttles testify to the personal and special significance or function of these objects. This can be compared to portraits of women wearing portrait miniatures of their husbands, placing them forward as part of their apparel, suggesting their allegiance both to fashion and spouse. [9] A portrait of Elizabeth de la Vallée de la Roche by Michel Pierre Hubert Descours (Fig. 5), for example, shows her holding a knotting shuttle in her right hand, tightly holding its string with her left, in which she wears a portrait miniature bracelet of her husband. The portrait is a socio-political statement, underlining her role as domestic and as her husband’s biggest support.

Fig. 4 Jean-Marc Nattier (1685-1766), Portrait of Madame Adélaïde de France Tying Knots, 1756, oil on canvas, Versailles

Fig. 5 Michel Pierre Hubert Descours (1741-1814), Portrait of Elizabeth de la Vallée de la Roche, 1771, The Bowes Museum

Though there may not be abundant evidence of women gifting knotting shuttles, letters and accounts from that era do mention the popularity of knotting and the exchanges of related items as gifts among women of the upper class. Jill Rappoport’s extensive book ‘Giving Women: Alliance and Exchange in Victorian Culture’ argues the importance of gift-giving in this period as a means to construct a woman’s female social network. In the act of creating and presenting these opulent objects, women ingeniously formed alliances that were built through the exchange of gifts. [10]

Étui

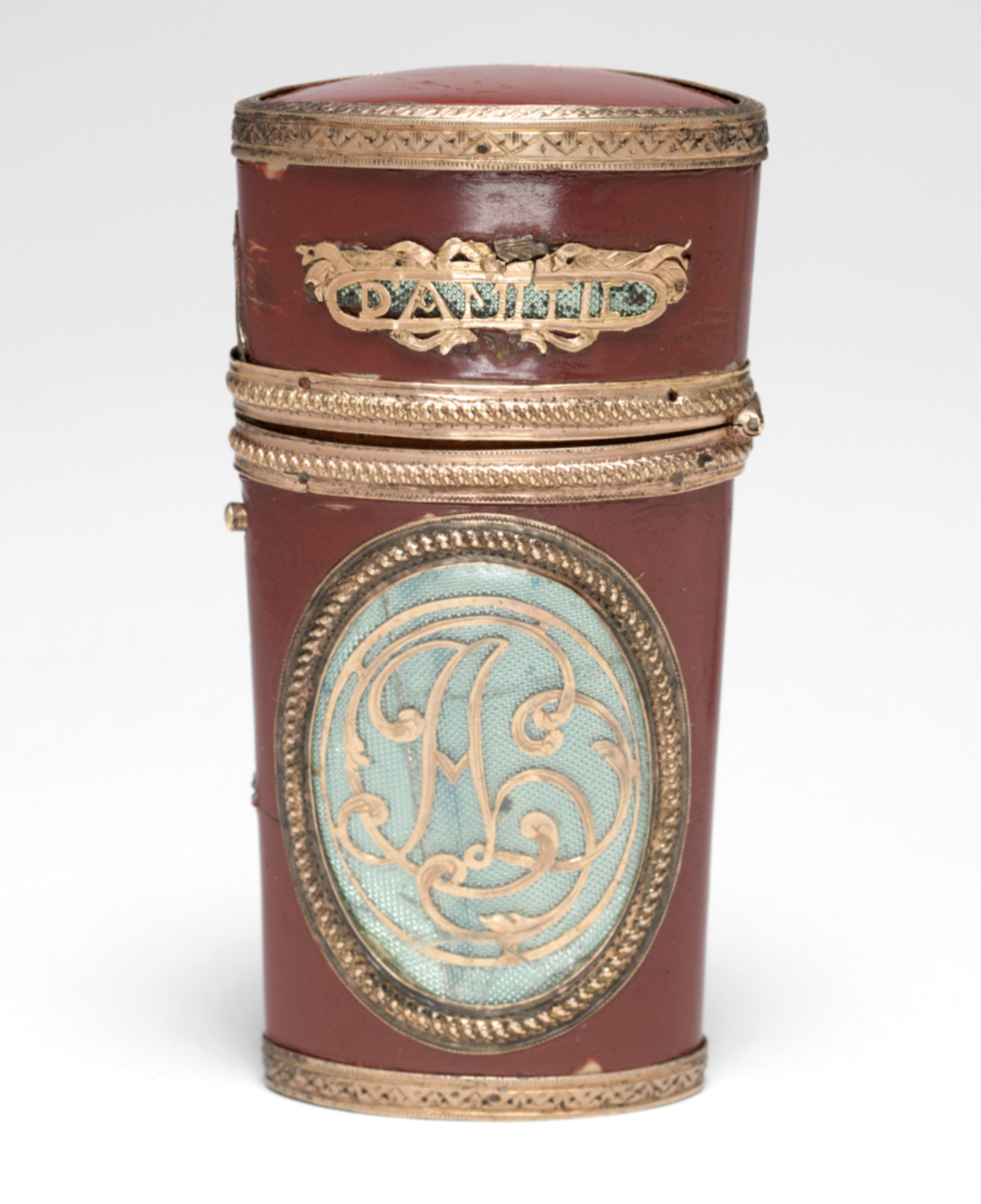

An Étui, more commonly known as a Nécessaire (Necessary in English), served as a compact repository for personal grooming items, including items such as a mirror, tweezers, an ear spoon, nail file, scissors, fruit knife, and scented perfume bottles. This pocket-sized assistant played a pivotal role in a well-born woman’s toilette, equipped with all the tools necessary for attending to aspects of domestic and social life. Despite a lack of scholarly attention on the commissioning and gifting of étui, recurring inscriptions strongly indicate their association with female friendship. Perhaps akin to the camaraderie observed when women collectively visit the bathroom today, these beautiful functional objects served as discreet gestures of solidarity and friendship.

Fig. 6 Étui, French box, Miniature by Gerard van Spaendonck, circa 1766, Fitzwilliam Museum

Fig. 7 Étui, enamel on copper with gilt metal mounts; oval in section with tapering sides, decorated in colours with four pastoral vignettes on a pink ground, circa 1760s, English style, Fitzwilliam Museum

An 18th-century étui (Fig. 6), illustrated with a miniature of a two-handled stone vase carved with a cherub, containing flowers including roses, hyacinth, auricula and morning glory, next to a nest of leaves containing three eggs, all on a marble slab, exemplifies the intricate craftsmanship of these items. On either side of the hinged lid is an inscription bearing the words “Necesair” and “D’amitié”. The gold openwork inscription cleverly plays with words, translating to “Nécessaire (as in the object) of Friendship” or a “Necessary Friendship”, suggesting the significance of these étui as tokens of companionship among women. Similarly, in the Isabella Gardner Museum, an etui (Fig. 8) bears the inscription “Souvenir D'Amitié”, (Memory of Friendship) reinforcing again the notion that these ornate yet functional accessories were often exchanged as meaningful gifts between women.

Fig. 8 Étui, Paper with silver, brass, and mother-of-pearl veneer, late 18th Century, French, Isabella Gardner Museum

In the British Museum, an 18th-century enamelled étui vertical box adorned with flowers features portraits of a young woman and man, likely siblings rather than romantic partners. This particular example presents a challenge in determining the gift giver. The étui has not been evidenced in betrothal gift-giving culture, therefore my own speculation is that it may have been owned by the mother and/or given to her daughter, making the étui a gift representing the next chapter of a woman in womanhood.

Fig. 9 Etui, enamel bust of a young man and woman; flowers on lid, 18th Century, The British Museum

Carnet-de-Bal

This brings us to the most common female accessory exchanged by and to women, which best exemplifies the notion of Women wearing Women; the carnet-de-bal.

Originating in early 18th-century Europe, particularly in Paris, the powerhouse hub of luxury goods production, the carnet-de-bal epitomised the pinnacle of collaborative luxury craftsmanship, featuring brilliant enamelling, intricate gold inscriptions and jewels. Often referred to as Souvenir, it emerged as a quintessential upper-class female accessory exchanged among women during the 18th century. The carnet-de-bal, more commonly known as the Dance Card in English, held both practical and symbolic significance, embodying both elegance and functionality. It was essentially a thin rectangular box with a hinged lid which could seamlessly fit ivory sheets and a stylus for writing. Roger Hourant’s research on the use of carnet-de-bal sheds light on its practical significance, documenting various dances and the etiquette surrounding invitations. The ivory tablets within the carnets were used by single ladies to meticulously record the order of the evening’s dances and promised partners, serving as a cherished mementos of social engagements and camaraderie.

Fig. 10 Carnet-de-Bal, with built-in clock, gold/enamel with diamonds, France, circa 1830. Provenance: Fondation Napoleon

An exceptional example of this artistry is a carnet adorned with an integrated watch, (Fig. 10) a rarity among dance card cases. This particular piece, once part of the Foundation Napoleon collection, boasts blue engine-turned enamel, an oval ivory miniature portrait surrounded by rose-cut diamonds, and a watch with an oval form movement and cylinder escapement. The inscriptions “Souvenir” on the front and “d’Amitié” on the back, both completely set with diamonds, elevate this piece to an extraordinary level of craftsmanship but more importantly exemplifies the epitome of luxury offerings in aristocratic society.

Fig. 11 Souvenir, gold, diamonds, pearls, enamel and ivory, French, 1776-7, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Other luxurious examples of carnet-de-bals, such as the one housed in the Metropolitan Museum in New York (Fig. 11) epitomise opulence with their gold construction, diamond-studded inscriptions and exquisite enamel work. Although the identity of the portrayed woman and artist remains unknown, the lavishness of such gifts suggests their esteemed value and significance within upper class female social circles. Other more common and less opulent examples which feature miniatures, by artists such as C. de Roy, Nadine Vallin and Louis Marie Sicardi, [11] further underscore the artistry and allure of these unique treasures, which captivated the hearts of recipients and collectors alike.

Fig. 12 Souvenir, Miniature attributed to Louis Marie Sicardi, 1770, gold, tortoiseshell, ivory, Metropolitan Museum

Fig. 13 Carnet-de-bal with miniatures of an unknown lady, circa 1790-95, enamel, gold, diamonds, ivory, Royal Collection

Fig. 14 Carnet-de-bal, miniature by C. de Roy, 1773-4, gold, ivory, Metropolitan Museum

Fig. 15 Souvenir, Miniature by Nadine Wallin (active 1787-1813), circa 1789, gold, lacquer, ivory, Metropolitan Museum

While I have emphasised the carnet as predominantly associated with women, there are examples which include a miniature portrait of a man. This particular example (Fig. 16) implies its potential as a gift from a man, possibly a secret lover. Attributed to Louis Cousin, [13] it first seems like an ordinary carnet, with aubergine guilloché enamel background and ivory frames decorated with allegorical scenes. However, it features a secret mechanism; the front panel slides out to unveil a hidden miniature portrait of a man. Despite the inscription “Souvenir D'Amitié”, it is probable that the man bestowed this carnet upon the woman who owned it. However, the narrative that a best girlfriend would offer such a risqué gift is more intriguing. A comparable item is an oval-shaped snuff box crafted in Dresden in 1775, now housed in the Wallace Collection. [14] This box also conceals a secret slide that, when drawn out, reveals a portrait of Voltaire on one side and his mistress Emilie, Marquise du Chatelet on the other. Unfortunately, research has determined that the miniatures were made later, the box never belonging to Voltaire, as it was made 25 years after Emilie’s death and when Voltaire was much older. Nevertheless, hidden portrait miniatures in snuff boxes were not uncommon, a notable example being a mid-18th century box with a secret compartment revealing a portrait of Charles Edward Stuart, acquired by the West Highland Museum in 2019. These are still much like a reliquary, encouraging exterior aesthetic and material contemplation whilst concealing the representation of an invaluable tangible – the relationship between two individuals. [15]

Fig. 16 Carnet-de-Bal with secret mechanism in gold, attributed to Louis Cousin, Paris, 1779. Provenance : Chateau du Perche.

While carnet-de-bals may have maintained a primarily French identity, their allure undoubtedly transcended borders, and likely found its way to England. The giving, receiving, and wearing of portrait miniatures as part of fashionable social practice was an important aspect of luxury in England, so it is more than likely to have accustomed to female accessories as well. The carnet-de-bal below for example, although French in style has an English gold inscription, “Keepsake” on either side of the lid.

The identity of the sitter and artist is unknown, but the inscriptions suggest ties to an English market. The use of dance cards gained tremendous popularity among European courtiers in the latter part of the 18th century and later was adopted in American ballrooms. The evolution of the carnet-de-bal into printed pasteboard booklets in the 19th century added a new dimension to its purpose. These booklets, hanging from silken cords on a lady’s wrist, became costly and elegant gifts exchanged among friends and lovers. They served as timeless and elegant reminders of shared moments and affectionate bonds, with inscriptions of “Souvenir D’Amitié” emphasising their sentimental value. Although they retained popularity through the initial decades of the 20th century, their decline began due to shifting cultural ideals. This era witnesses industrial and urban growth, the onset of global conflict, and the broadening of women’s roles in society. Consequently, the dance card came to symbolise a bygone era which could not be maintained.

Fig. 17 Carnet-de-bal, Portrait Miniature of a Lady, wearing white gown, her hair powdered, set into a vari-coloured gold and painted papier-mache carnet-de-bal; circa 1785, The Limner Company. https://www.portraitminiature.com/c122-carnet-bal.

Whether portrait miniatures were mounted on jewellery, tokens of affection, or on an accessory, it is easy to overlook how highly invested they were as artefacts in female social relations and in representation. Once mounted, a fundamentally private object enters social and economic exchange systems, actively participating and engaging in public life. [16]

Portrait miniatures are distinguished by the necessity of being both visually admired but also their fundamental role in being physically held. It is therefore essential to examine how the sense of touch is incorporated into these representational practices. The conscious design of these feminine accessories discussed reflects the significance of tactically and proximity between the body and the object. In navigating the landscape of 18th century functional luxury accessories, these portrait miniatures of carnet-de-bals reveal themselves not only as relics of personal emotions but also as tangible manifestations of the profound friendships that shaped the social fabric of the time. [17]

Specific examples of individual gifts exchanged between women may not be well-documented, however, one can look at the literary culture of Jane Austen for example which often include scenes of women exchanging small tokens or accessories as a sign of friendship. The concept of “inseparability” in female friendships described in Rousseau’s La Nouvelle Heloise (1761) also informs us of the extent women were involved in the realm of gift-giving culture. In the end, these reflect the common cultural practice of women exchanging gifts, a practice that Dr Leonie Hannan argues women were ‘highly implicated in the process of forming and maintaining friendships and familial connections abroad as well as at home.’ [18] As tokens of affection, remembrance, and alliance these ornate accessories preserve the spirit of female friendship, arguably the most profound friendship there is.

“The tablets we use to write are a kind of little book which has a few sheets of ivory, paper or prepared parchment, on which we write with a touch or a pencil the things you want to remember”

— Diderot

[1] See Jill Bepler and Svante Norrhem, Telling objects. Contextualising the role of the consort in early modern Europe, Wiesbaden, Harrasowitz Verlag, 2018, p. 9-16.)

[2] Scientific advancements, such as Jean Toutin’s revolutionary enamel painting technique, contributed to more affordable production, expanding the popularity of enamelled accessories beyond noble classes.

[3] Consultant Celine Cachaud shows how the display of the framing was directly linked to the technique of the miniature. In the beginning, the fragile structure of watercolours on vellum required to protect the miniature in boxes, closed medallions or precious cases, whereas with the development of the enamel technique, the portrait could be openly displayed and set in jewelled settings like a boîte à portrait.

[4] Montpetit refined this technique, often known as “eludoric”. These oil paintings were created on fine cloth (apparently under a thin layer of water) and then stuck onto the reverse side of an embossed glass with water-soluble glue (presumably animal glue).

[5] Roulston, Christine, ‘Separating the Inseparables: Female Friendship and its Discontents in Eighteenth-Century France’, p. 215

[6] Sawyer, Drew, Portrait Miniatures, Hair and the limits of Representation

[7] It must be noted that shuttles were very often gifted by husbands or partners, however they were also exchanged among women.

[8] Roulston, Christine, ‘Separating the Inseparables: Female Friendship and its Discontents in Eighteenth-Century France’, p. 217

[9] Pointon, Marcia. “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England.”, p. 50

[10] Rappoport, Jill, “Giving Women: Alliance and Exchange in Victorian Culture, Chapter 2

[11] Although his research is more geared towards carnet de bal in the 19th and 20th centuries, the functions would have not changed that much and would have had a similar approach.

[12] Sicardi was French miniaturist who worked in French court - known to have several portrait miniatures of Marie Antoinette, one of which being a portrait miniature of the Queen on a snuff box, last sold at Bonhams 26 April 2023

[13] Based on its similarity to a carnet-de-bal by Cousin, now in the Rijskmuseum, Amsterdam.

[14] There has been much debate on the legitimacy of this snuff box with two hidden portraits of Voltaire and Emilie du Chatalet, thought to be Dresden goldsmith Johann Christian Neuber.

[15] Pointon, Marcia. “‘Surrounded with Brilliants’: Miniature Portraits in Eighteenth-Century England.”, p. 60

[16] Ibid., p. 49

[17] Ibid., p. 62

[18] Jill Rappoport, “Giving Women: Alliance and Exchange in Victorian Culture, Chapter 2