Paramount Women

Portrait Miniaturists from 16th to the 19th Century

By Roxane Hemard | 6 March 2024

“Our native paintresses, as the old-fashioned art critics and compilers of biographical dictionaries quaint them, have left but faintly impressed footprints on the sands of time. They do not glitter in the splendour of renown, like their sisters of the pen or of the buskin.”

— Ellen Creathorne Clayton, English Female Artists, 1876 —

Tracing the life stories of female painters from the 16th to even the 19th century is often rather challenging. Common hindrances include a scarcity of primary sources and the consequences of marriage, where women not only risked losing the opportunity and capability to work but also faced the potential overshadowing of their contributions by their husbands’ personal, economic or even artistic identities. In celebration of Women’s History Month, this blog aims to spotlight the often-overlooked contributions of women in the realm of portrait miniatures, shedding light on just a few women and their legacy in the world of art. Despite the remarkable talents of these women miniaturists, their achievements have been obscured by the overall historical neglect of women artists. While efforts to reclaim the importance of female artists through exhibitions and scholarly interest are underway, the scarcity of documentation on their lives and oeuvres poses a significant challenge in rewriting history. The everlastingness of a reputation hinges on the survival and accessibility of their artworks, as well as subjective assessments of their value. A reluctance persists even today in acknowledging the existence of other women painters, possibly because their existence runs counter to preconceptions of early modern society. [1]

Levina Teerlinc (1510s-1576)

Fig. 1. A Girl, formerly thought to be Queen Elizabeth I as Princess, 1549, attributed to Levina Teerlinc © Victoria and Albert Museum

Levina Teerlinc was one of the most important Renaissance miniaturists who played a crucial role at the English court between Hans Holbein the Younger and Nicholas Hilliard. Born in Bruges, Teerlinc was one of five daughters of Simon Bening, a renowned Flemish illuminator and miniaturist (considered one of the last major artists in the Netherlandish tradition), and his first wife Catherine Stroo. Levina first arrived in England in 1546, appointed as the replacement limner for Lucas Hornelbolt, [2] the ‘King’s Painter’ and court miniaturist who had died two years prior. Remarkably, Henry VIII took the unprecedented step of naming Teerlinc as the ‘King’s Paintrix’, making her the first woman in Europe to hold an official artistic position at the English court. Not only was this title a monumental achievement in itself, but Teerlinc achieved considerable financial success as the court painter, surpassing even Holbein’s earnings during his tenure. Beyond her role as a court artist, Teerlinc gained prestige by serving as a gentlewoman for Mary I and as a gentlewoman of the privy chamber for Elizabeth I, recruited to the court of Henry VIII by his last wife, Katherine Parr (perhaps at the instigation of her sister Anne Herbert).

Attributing works to Teerlinc with certainty remains challenging due to the fact that she did not sign a large majority of her works. Lack of documentation has led art historians to disagree on attributions, with some suggesting that, as a gentlewoman at court, her involvement in painting may have been minimal. Mr. Foster (British Miniature Painters, p. 12) suggests that many of her miniatures were destroyed in the fire at Whitehall, and also that some of them are concealed under the name of Holbein. [3]

Fig. 2. Mary Dudley, Lady Sidney (d.1586), c.1575 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 3. Self Portrait, Simon Bening (c.1483-1561), 1558 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Written in gold on a red background is an inscription; “"Simon Bennik, the son of Alexander, painted this himself at the age of 75 in 1558."

Fig. 4. An Unknown Woman, c.1560 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 5. Princess Elizabeth Tudor, 1550-51 © Royal Collection, Windsor

Fig. 6. An Elizabethan Maundy, c.1560, Private Collection

Fig. 7. Katherine Grey, Countess of Hertford © Victoria and Albert Museum

One of the most interesting discourses has revolved around Teerlinc’s relationship with Nicholas Hilliard. Both Roy Strong and Jim Murrell, experts in the field of 16th-century miniatures, suggest that Teerlinc actually taught Hilliard the art of limning. [4] It remains uncertain whether Teerlinc ever even crossed paths with Nicholas Hilliard, let alone collaborated with him. However, scholars have pointed to Hilliard’s initial miniature of Elizabeth, dated 1572, a period during which Teerlinc served at the queen’s court. Some have argued that the Ghent-Bruges school, where Teerlinc received early training, was inherently characterized by collaboration, and as such the ethos from this collaborative tradition stayed with Teerlinc’s entire life.

Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1531-1625)

Fig. 8. Miniature Self Portrait, c.1556 © Museum of Fine Arts Boston

In the cinquencento, Sofonisba Anguissola’s self-assurance and fearlessness as a female artist were unprecedented and impressive for the time. Rather than adhering to established conventions, she continuously challenged them, distinguishing herself by exploring innovative styles of portraiture, breaking gender barriers in the male-dominated art world.

Born into a minor impoverished nobility in Cremona, Italy, Sofonisba’s career afforded her an extraordinary trajectory, ultimately becoming a lady-in-waiting to the Queen of Spain, Elizabeth de Valois. Her father, Amilcare Anguissola, recognised her artistic talents early on and encouraged her and her sisters to receive a quality education in the arts and sciences. At 14, she became a student of Bernardino Campi, a prominent painter in Cremona, before moving to Milan to study with Bernardino Gatti. At the young age of 26, she received an invitation to join the influential court of Philip II as a painter, marking the beginning of her international career.

Fig. 9. Self portrait miniature attributed to Anguissola, c.1550-1620 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 10. Portrait of a girl from a noble family, last sold Christie’s January 2019

Fig. 11. Self portrait, c.1556, oil on panel © Fondation Custodia, Collection Frits Lugt, Paris.

Her self portraits stand out as the most captivating facets of her body of work. The most famous (for good reason) now housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and painted around 1556, showcases her artistic prowess [fig. 8]. It is exceptional in terms of composition and meticulous technique. Dressed in the black attire that characterizes most of her self portraits, Anguissola sits against a dark green background, wielding a shield with a complex monogram – possibly containing her family motto or a reference to her father, Amilcare. [5] The Latin inscription around the rim of the medallion reads,

“The maiden Sofonisba Anguissola, depicted by her own hand, from a mirror, at Cremona”.

This miniature not only showcases Anguissola’s meticulous technique but also reflects her daring wit, and nonchalance. This self portrait, positioned almost as a manifesto, amplifies Anguissola’s strength as a revolutionary female artist, one who positioned herself at the same level as her male counterparts, if not higher. [6]

Susannah-Penelope Rosse (1652-1700)

Fig. 12. A Woman, presumably a Self Portrait, ca. 1680 © Victoria and Albert Museum

British painter Susannah-Penelope Rosse had an impressive lineage as the daughter of Richard Gibson, known as ‘Dwarf Gibson’. A British miniature painter and court dwarf, her father held his position during the reigns of Charles I, Charles II and William III. He also instructed the Princesses Mary and Anne, daughters of the Duke of York, in drawing. [7]

Growing up in London, Susannah-Penelope was intimately connected with the artistic milieu, forming a lasting friendship with the highly esteemed artist Samuel Cooper. In addition to her admiration for Cooper, Rosse showcased her talent by reproducing some of Mary Beale’s portraits into miniatures, a notable example being a portrait of the poet Elizabeth Singer Rowe. She painted numerous members of the court of Charles II, attaining such popularity that, in a remarkable incident in 1682, she shared a sitting with the eminent Sir Godfrey Kneller for a portrait of the ambassador from Morrocco. [8]

Fig. 13. Portrait miniature of a Gentleman, thought to be Edward Montagu, 1st Earl of Sandwich (1625-1672), c.1674, The Limner Company

Much akin to the collaborative endeavours of Charles and Mary Beale, Susannah-Penelope and her husband Michael Rosse constituted a formidable professional team. Michael, raised in Covent Garden near the Beales, pursued a career as a jeweller to the crown, possibly framing many of his wife’s exquisite miniatures.

In the sale of Michael Rosse's collection of art in 1723, over 20 years after her death, numerous original works by Cooper and acknowledged copies of Cooper by Susannah-Penelope were found. The inclusion of unfinished works by Cooper allowed her to closely study his technique. According to George Vertue, she initially learned her craft from her father but was captivated by Cooper's artistry, dedicating herself to studying and emulating his limnings to perfection.

Fig. 14. Louise Renée de Penancoet de Keroualle, Duchess of Portsmouth, c.1682-5 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 15. Portrait of a Lady, called Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, c.1690-95 © The Royal Collection

Fig. 16. Mrs. Pru Phillips, c.1690 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 17. Mrs Priestman, c.1690, © Victoria and Albert Museum

Rosalba Carriera (1673-1757)

Fig 18. Portrait miniature of a Gentleman wearing armour breastplate and blue cloak, holding the Coronation Medal of George I, c.1715. The Limner Company

Rosalba Carriera, a legendary figure and trailblazer, emerged as one of the foremost European portrait painters during the first half of the 1700s. Born to a clerk and a lace maker, she potentially learned the craft of lace-making from her mother. A declining industry, Carriera embarked on a more profitable artistic venture in Venice, adorning snuff boxes for tourists.

By the age of 25, Rosalba earned special membership in the Academy of St Luke in Rome, being made an ‘accademico di merito’, (a title reserved for non-Roman painters), fuelled by the success of her initial miniatures and phenomenal pastel works. [9] Her exceptional talent attracted numerous foreign courts and clients, prompting some to travel specifically to Venice just for a sitting. Notably, Prince Frederick Augustus II of Saxony, later King Augustus III of Poland, sat for her in 1713, amassing a substantial collection of over 100 pastels in Dresden (to this day the largest collection of Rosalba pastels).

In 1720, encouraged by collector Pierre Crozat, she left for Paris, where her realism [10] and soft colors, integrated into the Rococo style, captivated the French. In less than one year, she received 36 commissions, producing over 50 portraits, among them one for Louis XV as a child. [11] She began to interact with numerous French artists, notably Antoine Watteau, who honoured her with a request for one of her works. [12] Her influence significantly contributed to shaping the prevailing tastes in 18th-century France, in its graceful forms, delicate colouring and vaporous effects, so often poetic in origin. During a 6-month stint in Vienna in 1730, Rosalba found patronage in Holy Roman Emperor Charles VI, with the empress becoming her pupil as a result.

Fig. 19. Self-Portrait as 'Innocence', c.1705-1757 © The Royal Collection

Fig. 20. A young Girl, holding a rabbit, possibly in an allegory of ‘Autumn’, c.1715, Philip Mould & Company

Fig. 21. Woman with a Dog, c.1710-20 © Cleveland Museum of Art

Fig. 22. Portrait of Marco Ricci, c.1724 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 23. Rinaldo and Armida, last sold Chiswick Auctions December 2021

Fig. 24. Portrait of a Man, c.1710 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

It is widely regarded that Carriera developed the art of painting miniatures on ivory, in place of the conventional vellum (animal skin). Her innovative technique, known as ‘fondelli’, involved watercolour on ivory, mimicking the delicate allure and softness of her pastels. Unlike more traditional methods, she painted miniatures with brushes and strokes rather than with a needle, one point at a time. [13]

At only 30 years old, she had established a successful studio for miniature portraits and mythological scenes on ivory. Despite her international acclaim, her eyesight began to deteriorate in the 1740s, and by the 1750s, she had almost completely lost her sight. Unmarried, she passed away at 84, leaving an estate ten times larger than the renowned Venetian painter of the time, Canaletto.

Penelope Carwardine (1730-1801)

Fig. 25. Portrait of an Unknown Woman, c.1760 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Penelope Carwardine was one of eight children born to John Carwardine and Anne Bullock. Her mother was also a miniature painter, and together, they showcased their miniatures at the Incorporated Society of Artists in London in 1761 and 1762 under the name Mrs Thomas Carwardine (Anne).

The family faced financial challenges due to John Carwardine’s mismanagement of the family estates, and Penelope turned to miniature painting as a means to support her family. She exhibited her work at the Society of Artists, marking her independence foray into the art scene. Some scholars have suggested suggest that she ceased her artistic pursuits after marrying James Butler in 1763. Despite this claim, evidence from the Society of Artists indicates that some of her works were exhibited as late as 1772. [14]

According to Dictionary of National Biography and other historical sources, she received instruction in miniature painting from Ozias Humphry, [15] mastering the art by 1754. However, there is much discrepancy in timeliness, as Humphry was not born until 1742. This raises the question and possibility that historical sources may have conflated details, and it could be that Humphry was actually a pupil of Carwardine. Nevertheless, she aligned herself with the Modest School of English miniaturists, [16] a group that included notable artists such as Peter Paul Lens and Gervase Spencer.

Carwardine enjoyed a close friendship with both Sir Joshua Reynolds and Frances Reynolds, with Joshua Reynolds even painting a portrait of one of her sisters as a gift. Many of her miniatures remained within her family’s possession until 1887, along with three portraits of Carwardine: one by Thomas Bardwell in 1750, another by a Chinese artist around 1756, and the third by George Romney in circa 1790.

Fig. 26. Portrait of a Lady looking in a mirror - Karen Taylor Fine Art

Fig. 27. A Lady, wearing white chemise, last sold Bonhams November 2014

Fig. 28. Portrait of a Lady, Rosebery’s London, previously in private collection

Fig. 29. Maria Gunning (later Countess of Coventry), c.1757 © Wallace Collection

Fig. 30. George Anson Nutt (1750-1828), c.1758, Tormey-Holder Collection

Anne Mee (1770-1851)

Fig. 31. Lady Isabel Anne Dashwood (1772-1858), c.1793, last sold Chiswick Auctions, March 2020

Anne Mee hailed from a family with financial constraints, and financial worries would endure throughout her life. Anne’s father, John Folstone, a copyist of pictures, [17] exhibited at the Society of Artists of Great Britain from 1769-70 and at the Royal Academy from 1771 to 1783, specialising in small portraits, often executed at the sitter’s location.

Anne’s father passed away early in her life, leaving her as the eldest among eight siblings, and she took-up painting professionally to support her large family. Horace Walpole highlighted Anne’s familial responsibilities, noting that she worked incessantly to sustain her mother and eight siblings. He wrote in a letter,

“I have got a solution of Miss Foldsone: she has a mother and eight brothers and sisters, who make her work incessantly to maintain them, and who reckon it loss of time to them, if she finishes any pictures that are paid for beforehand—That however is so very uncommon that I should not think the family would be much the richer. I do know that Lord Carlisle paid for the portraits of his children last July and cannot get them from her-at that rate I may see you before your pictures!” [18]

Fig. 33. Self Portrait, c.1795 © Victoria and Albert Museum

Fig. 33. Queen Charlotte (1744-1818), attributed to Anne Mee © The Royal Collection

Fig. 34. Lady Louisa Atherley (1765-1851), c.1795, last sold Olympia Auctions, November 2023

Fig. 35. Portrait miniature of a child, c.1795, The Limner Company

Despite financial hardships, Anne received an education at Madame Pomier’s school in Bloomsbury. Displaying remarkable talent from a young age, she commenced her artistic journey at the age of 12, financed and guided by the tutelage of George Romney. Her talent was evident, and during the early 1790s, she worked at Windsor Castle under the patronage of the Prince of Wales, later George IV. Her miniatures reflected influences from artists in the Prince’s circle, notably Richard Cosway. The then Prince Regent employed Anne to paint portraits of fashionable beauties, many of which found a place at Windsor. Some of her portraits were engraved for publications like the Court Magazine and La Belle Assemblée. In 1812, she initiated a serial publication, the Gallery of Beauties of the Court of George III, which featured her own portrait at the forefront, although only one issue was released. Her portraits are often characterised by large eyes, and by 1804 she was able to ask as much as 40 guineas for a miniature.

Anne Mee’s significance lies in being one of the few professional female miniaturists in the early 19th century. Even after her marriage to Irish barrister Joseph Mee, she defied the norm of many female artists who ceased working post-marriage. However, her husband imposed restrictions, allowing her to paint only ladies without the presence of gentlemen during sittings, as noted by diarist Joseph Farington.

Madeleine Pauline Augustin (1781-1865)

Fig. 36. Portrait miniature artist’s brother, Alexandre Nicolas Ducruet (1788-1858), seated reading next to a fireplace; circa 1830, The Limner Company. The work shown here, datable from the sitter’s costume as circa 1830, can be recognised as Alexandre by his distinct facial hair. Pauline was incredibly fond of her brother, spending a lot of time together at Pauline’s country estate Courtoiseau, painting miniatures of their entourage.

From the 16th to the 19th century, many painters’ wives engaged in miniature painting, skillfully replicating their husbands’ paintings in smaller formats, as exemplified by Madeleine Pauline Augustin.

Born in Paris in 1781, she was the daughter of Germain du Cruet, Chevalier de Barailhon, one of the numerous secretaries to King Louis XVI. Although her early education is unclear, it is believed that she studied painting with her godmother, the highly recognized 18th-century still life painter, Anne Valleyer-Coster. It was unusual in this period for women to begin their career studying with another female artist – usually a male member of the family gave instruction. In this case, her godmother must have been a source of inspiration both artistically and professionally.

Fig. 37. Portrait of a Man, possibly a member of the Gounod family, c.1835, last sold Sotheby’s April 2015

Fig. 38. Portrait of a Woman, 1835 © Galeries les Portraits en Miniature

Fig. 39. Portrait of a Woman, Private Collection.

In the 1790s, Pauline entered the studio of renowned miniature painter and (later in 1814) Premier Peintre of Miniatures to Louis XVIII, Jean-Baptiste Jacques Augustin. Augustin had gained tremendous notability for establishing a drawing academy that nurtured talented miniaturists, helping solidify his reputation as one of the most influential miniaturists of the late 18th century. Their relationship deepened, and in 1800, Pauline and Augustin married in Fussyny where her family had property. She was not only quickly regarded as her husband’s best pupil but was considered an important collaborator and artistic partner. Her ability to adopt her husband’s style to such a meticulous extent has made it so it is often impossible to distinguish her works from his.

Pauline was highly regarded in the Paris Salons where she started exhibiting in 1822 with miniature portraits of her husband and painter friends such as Merry-Joseph Blondel and Abel de Pujol. In 1824, she exhibited a portrait of Belgian violinist Lambert Massard which earned her a medal of the second class. She continued to exhibit regularly in the Paris Salons of 1827, 1831, 1834, 1835 and 1838. It was during this time, not much longer after her husbands’ death, that she retired to Arras until her death in 1865, surviving her husband by almost three decades. Pauline’s miniature portraits are now exhibited all over the world, from the Metropolitan Museum in New York to several European collections.

Anne Langton (1804-1893)

Fig. 40. Martha Walsh (née Bellingham), 1832, The Limner Company. Although the majority of her extant portrait miniatures portray her immediate family, the sitter here can be identified as Martha Bellingham, and may have represented an important paid commission for Langton. The portrait here may have been a commission to celebrate the marriage of Martha and General Walsh, an acquaintance of Langton’s brother.

Born in England, the artist Anne Langton (1804-1893) is best known for her time in Canada, where she moved with her family in 1837. The Langtons settled on the frontier in Upper Canada, present day Ontario, where Anne recorded both the difficult and joyous times (in her drawings and written journals) within a close-knit pioneer community. [19]

At Anne’s birth, her prosperity and genteel status appeared permanent. Her father, Thomas Langton, had established himself in the hemp and flax trade and with the fortune he acquired, purchased Blythe Hall, near Ormskirk. It is within this exquisite mansion that Anne was raised. In 1815, when Anne was eleven, the family took off on a tour of the cultural centres of Europe to enhance their children’s education and awareness. Yet the collapse of the family business in 1821 abruptly ended the Langton family’s ardent pursuit of culture and learning. Blythe Hall was hastily sold, and the family moved to a small house in Liverpool, where Anne’s marriageable years were steeped in escalating poverty. Throughout the 1820’s and 1830’s, Langton grew familiar with the use of watercolour on ivory, the medium through which she created her miniature portraits. She had been introduced to this technique in Paris, and had continued to receive training under Thomas Hargreaves, R.A, a notable miniaturist working in Liverpool. Despite adversity, Anne incessantly devoted herself to art, providing testimony to her claim as an artist in her own right.

Fig. 41. Self Portrait, 1833 © Image from Archives of Ontario, REF F 1077-7-1-0-2

Fig. 42. Self Portrait, 1840 © Image from Archives of Ontario, REF F 1077-7-1-0-17

In 1950, one of her Canadian nephews, H. H. Langton, published an edited collection of Anne’s letters to her family and friends back in England. A Gentlewoman in Upper Canada exposes in great detail Anne’s experiences as a settler in North America, bringing her art into a broader social context. As a single woman both in England and in Canada, her letters reveal her incredible ambition and how she negotiated her roles as a gentlewoman, a colonial settler, a devoted daughter and aunt, and of course, a brilliant artist. [20] As Anne herself stated, her journals and sketches gave ‘some sort of a notion what this world of ours is like.’ [21]

Sarah Goodridge (1788-1853)

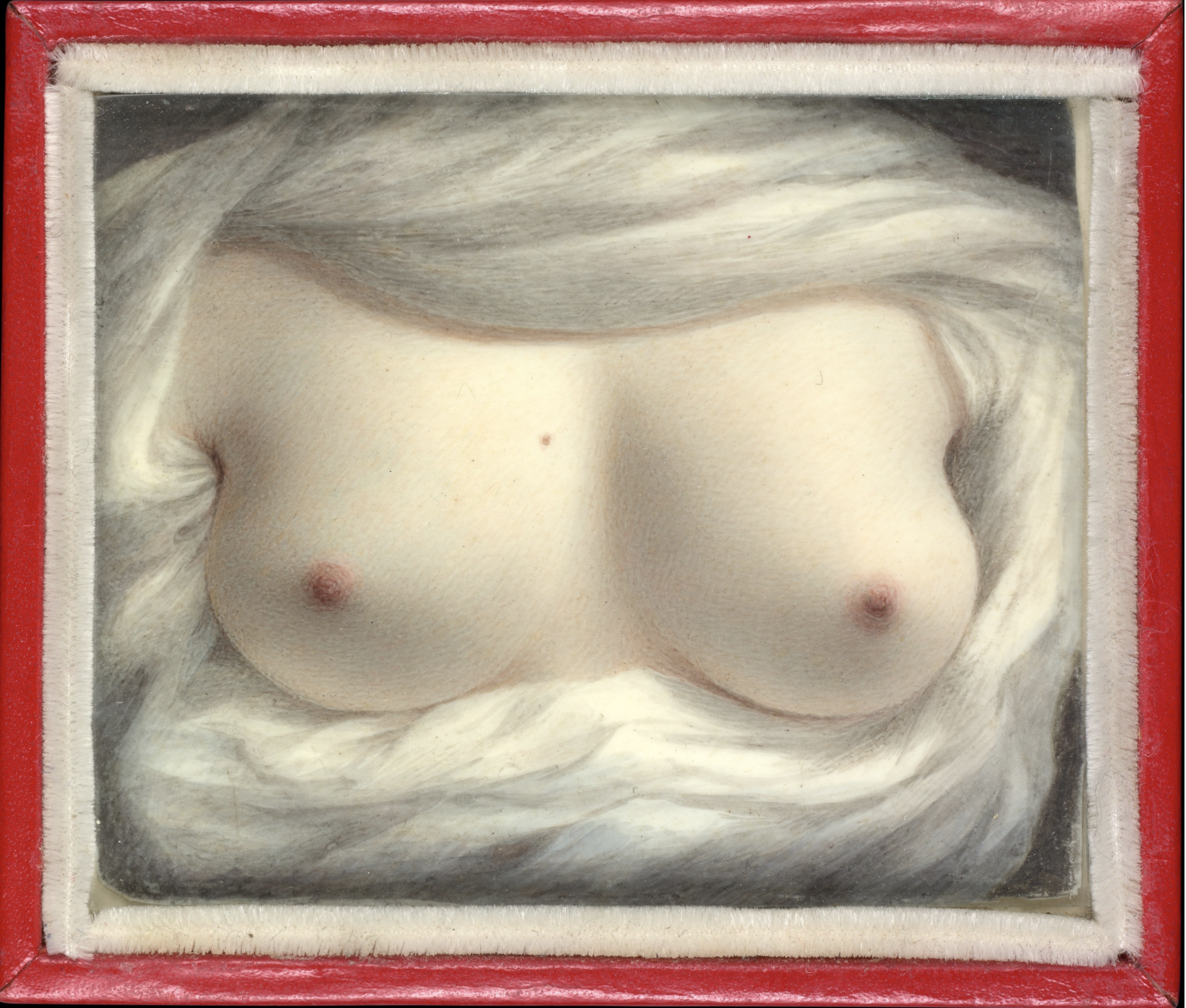

Fig 43. ‘Beauty Revealed’, 1828 © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

To conclude this discussion on remarkable female miniaturists, let’s delve into the story of Sarah Goodridge, a fabulous woman who displayed extraordinary courage through her self portrait, now known as ‘Beauty Revealed’.

Raised as one of nine children on a Massachusetts farm, Sarah was primarily self-taught, copying pictures on her mother’s kitchen floor. [22] Seeking to sustain herself as an artist, she moved to Boston in 1820 with her sister, immersing herself in the city’s artistic milieu, studying under leading American portraitist Gilbert Stuart. Her early sketches, created on birch bark due to a lack of resources for paper, showcased her nascent talent. She gained tremendous popularity, and transitioned to specializing in ivory, producing up to three portrait miniatures weekly. Through her commissions, she supported herself but also provided for her aging mother back home. By 1820, Sarah had established her own studio, making a successful career as an unmarried female artist, defying social expectations.

Sarah’s love life would inspire one of the most iconic self portraits ever created. A romantic relationship blossomed between Sarah and one of her sitters, a prominent lawyer and politician, Daniel Webster. This relationship was, however, complicated as Webster had an existing marriage and family. Their connection endured for years, with Sarah creating multiple portraits of her lover, tirelessly exchanging letters (she preserved his letters to her, while he, more mindful of his reputation, destroyed hers.)

Following the death of Webster’s first wife in 1828, Sarah most likely hoped for a change in their relationship. In a bold move, she painted a unique miniature, deviating from the prevalent trend of exchanging lover’s eyes or lips in miniatures. Instead, she presented an intimate yet audacious glimpse of her bared breasts, perhaps an allusion to her heart as well. [23] Daniel, known as ‘Black Dan’, had political and societal ambitions, and as such wanted to marry a woman of high advantage and status as opposed to an artist, marrying Caroline LeRoy in 1829. Despite Sarah’s unrequited love (at least legally), Daniel’s feelings for the young artist were profound. After his death in 1852, his children discovered Sarah’s suggestive miniature in his pocket, perhaps proof of his deep affections towards her all along.

Fig. 44. Self Portrait, 1830 © Museum of Fine Arts Boston

[1] Linda Nochlin, Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?

[2] Hornebolt’s daughter, Susannah Hornebolt, was also an exquisite illuminator. Albrecht Durer in meeting her father noted in his diary “Master Gerard, illuminator, has a young daughter about eighteen years of age; her name is Susannah; she had made a coloured drawing of Our Saviour, for which I gave her a florin; it is wonderful that a female should be able to do such work.” Ellen C. Clayton, English Female Artists, pg 6

[3] Simone Bergmans. “The Miniatures of Levina Teerling.” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 64, no. 374 (1934): 232–36. pg 232

[4] Ibid.,

[5] Art historian Patrizia Costa suggests the monogram might contain a coded family motto.

[6] Unfolding the Overlapping Bodies: An Analysis of Sofonisba Anguissola’s Self- Portrait Miniature in Boston as a Feminist Manifesto, pg 65

[7] Ellen C. Clayton, English Female Artists, pg 57

[8] Ibid.,

[9] The connoisseur Christopher Cole, secretary to Joseph Smith, English consul to Venice, introduced her to the medium of pastel in 1703.

[10] Rosalba Carriera. “A Young Lady with a Parrot, c. 1730.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 26, no. 1 (2000): 30–93. pg 8. She enhanced but never obscured the actual appearance of her sitters. In contrast, her allegorical types are often quite generalized.

[11] Sani, Bernardina. “Rosalba Carriera’s ‘Young Lady with a Parrot.’” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 17, no. 1 (1991): 75–95. pg 75

[12] Ibid.,

[13] In her pastels as well, she was considered by her contemporaries as innovative in her technique. She was the first to soften figures with extensive stumping or rubbing with a cloth, which later evolved into her “dry-brush” technique by dragging the flat side of her chalk lightly over a contrasting color to suggest diaphanous materials. Rosalba Carriera. “A Young Lady with a Parrot, c. 1730.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 26, no. 1 (2000): 30–93. pg 8

[14] Algernon Graves, The Society of artists of Great Britain, 1760-1791; the Free society of artists, 1761-1783 ; a complete dictionary of contributors and their work from the foundation of the societies to 1791, pg 53

[15] Anderson galleries, The art collections of the late Viscount Leverhulme, part two, paintings, pg 178

[16] Perfect Likeness : European and AMerican Portrait Minaitures from the Cincinnati Art Museum, pg 115

[17] Daphne Foskett, Miniatures, Dictionary and Guide, 38

[18] The Letter was sent in 1791 to Miss Berry, All Things Georgian, Anne Mee, Sarah Murden, 2015

[19] Errington, J. (2009). [Review of the book A Gentlewoman in Upper Canada: The Journals, Letters, and Art of Anne Langton]. The Canadian Historical Review 90(3), 552-553

[20] http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/langton_anne_12E.html [accessed 07/10/2020]

[21] A Gentlewoman in Upper Canada: The Journals, Letters and Art of Anne Langton (review), Katherine M.J. McKenna [accessed 07/10/2020]

[22] According to the artist's sister Eliza, who also became a miniature painter, Sarah began studying art by reading a book on drawing and painting. https://collections.mfa.org/objects/31073

[23] Barratt, Carrie Rebora, and Lori Zabar (2010), American Portrait Miniatures in The Metropolitan Museum of Art